By far the greatest flow of newness is not innovation at all. Rather, it is imitation.

— Theodore Levitt

When a company — for the first time in its history — presents a product that offers a new capability that a competitor had already introduced to the market a year earlier, should that be considered an innovation or an imitation?In his 1966 HBR article "Innovative Imitation" Theodore Levitt makes the following distinction:

Innovation may be viewed from at least two vantage points: - newness in the sense that something has never been done before, and

- newness in that it has not been done before by the industry or by the company now doing it.

Strictly defined, innovation occurs only when something is entirely new, having never been done before.

A modest relaxation of this definition may be allowed by suggesting that innovation also exists when something which may have been done elsewhere is for the first time done in a given industry.

On the other hand, when other competitors in the same industry subsequently copy the innovator, even though it is something new for them, then it is not innovation; it is imitation.

The newness of which consumers become aware is generally imitative and tardy newness, not innovative and timely newness.

Imitation is not only more abundant than innovation, but actually a much more prevalent road to business growth and profits.

Hence the categorization of a new offer as innovation or imitation depends on the definition* of the term "innovation" you adopt - according to the 2007 research paper "Innovation and Imitation as Sources of Sustainable Competitive Advantage".

That paper addresses the following research questions:

- What are the differences between innovating and imitating?

- What factors explain these differences?

- Can imitation be a source of sustainable competitive advantage?

Companies with what the authors call an entrepreneurial orientation tend to generate their own ideas (innovation) rather than to adopt ideas generated by others (imitation).

The authors define innovation as a form of technological development that expands not only a firm’s existing knowledge set but also the existing world knowledge set, whereas imitation is defined as the form of technological development that expands the firm’s existing knowledge set but not the existing world knowledge set.

Innovation expands the knowledge existing in the world,

Imitation expands only the knowledge existing in the company that adopts something new.

Three factors: Generation of ideas, timing, and space

The generation of the idea is the starting point for distinguishing between innovation and imitation. Only those companies that generate new ideas can be analyzed as possibly innovative, whereas those that take a previously existing idea should be considered imitators.

The generation of the idea is the necessary condition for obtaining an innovation, but this is not a sufficient condition in itself because, for innovation rather than merely invention, this idea must be put into practice (Damanpour; Schumpeter; Utterback).

The factor of timing must be considered for the differentiation of the two concepts, because generating a new idea means being the first to implement it and launch it on the market.

Innovation must be new for the organization and for its environment of reference. This consideration introduces the variable space (in effect, the global marketplace). This allows to separate the company that generates the idea, produces it, and applies it for the first time anywhere (the innovator) from another (an imitator) that later applies and markets that same idea.

One should distinguish between a company that follows the innovator in the same market (an imitator) and another that adopts an innovation so as to launch it in a different or new market segment or territory.

These three factors, the generation of ideas, timing, and space, help establish a typology of innovators and imitators that corresponds better to the real world.

Organizational attitudes:

Entrepreneurial, Market-oriented

The literature distinguishes between entrepreneurial and market-oriented organizational attitudes as factors influencing innovation.

Companies with an entrepreneurial orientation are “exploiters” of the knowledge generated by the “explorations” of their scientists or R&D personnel, which leads them to propose new ideas that are brought into material form as new products, services, or processes.

They have a greater propensity to generate their own ideas (innovation) rather than to adopt ideas generated by others (imitation).

Entrepreneurial orientation is defined as the approach characterized by

- Innovativeness

(defined as the tendency of an organization to support experimentation and creative processes intended to give rise to innovations), - High-risk projects, and

- Proactivity.

A proactive attitude or stance is identified with technological leadership and with the desire to be first or a pioneer.

The degree of risk incurred by launching an innovation is much greater than that accepted by the company that adopts an imitation because the innovator confronts a change in the knowledge existing at the global level, and incorporates the commercial risk and the technological risk inherent in true innovation.

An essential prerequisite for the development of successful innovations is a good knowledge of the industry and markets in which the organization operates.

Market orientation is the concern with or study of the business environment in general, including customers, competitors, suppliers, and other external forces that affect the behavior of the organization. Market-oriented companies continually modify their offer —their products, services, and processes—to satisfy the needs of their market.

Market-oriented companies with a corresponding focus on their clients ("proactive") have a greater propensity to generate ideas to satisfy their customers’ needs and innovate. Conversely, those companies with a focus on competitors ("reactive") have a greater propensity to adopt ideas generated externally and imitate.

Radical innovations emanate from scientific research supported by an entrepreneurial orientation. On the other hand, the strategy aimed at continually satisfying customer needs, characteristic of a market-oriented company, will lead to specialization in the development of incremental innovations.

Incremental innovation can be classified as a “pull”-type innovation, whereas a “push”-type innovation is radical innovation.

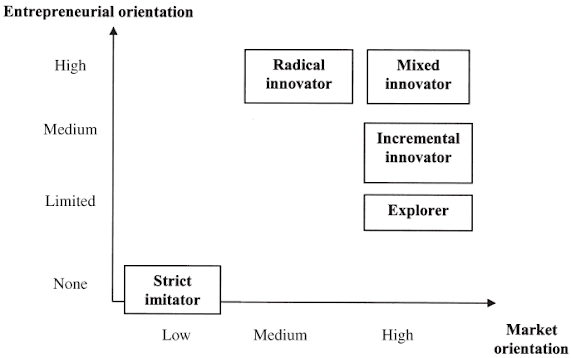

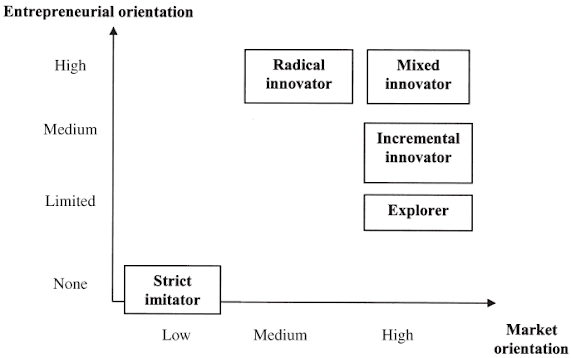

Topology of innovative and imitative companies

“Incremental innovator”

- Strong market orientation

- Moderate entrepreneurial orientation (proactive attitude)

- Moderate levels of technological and commercial risk

"Radical innovator”

- Moderate market orientation

- Strong entrepreneurial orientation

- High levels of technological and commercial risk

“Mixed innovator”

- Strong market orientation

- Strong entrepreneurial orientation

- Moderate levels of technological and commercial risk

“Strict imitator”

- Weak market orientation

- Lack of entrepreneurial orientation (reactive attitude)

- Low technological and commercial risk.

“Explorer”

- Strong market orientation

- Limited entrepreneurial (proactive attitude)

- Low levels of technological risk and moderate levels of commercial risk

The authors define global innovation as an innovation that is new for the economy as a whole and local innovation as an innovation that is new in a limited environment.

They distinguish between companies that imitate and operate in the same markets as the innovators, and those that do so in different markets.

In the same markets, taking into account the factor of timing, they argue that only the first to generate an idea and apply it as a new product should be considered an innovator, and that all the rest are imitators.

A company that adopts an innovation that is new for the company but has already been successfully applied or marketed in its reference market will be considered an imitator in the strict sense, whereas a firm is categorized as an explorer company if it introduces innovations in a market different from that supplied by the strict innovator company.

A previous article in this blog provides alternative views on how to construct a Typology of Innovation that imposes lesser requirements on the originality of an idea behind a specific type of innovation.

Competitiveness

Please consult the original article for an analysis of how both innovation and imitation can be a source of sustainable competitive advantage, provided the company is capable of designing a strategy that differentiates it from the innovator.

The establishment of barriers to imitation promotes the maintenance of the competitive advantage achieved by the successful innovator, provided this innovation is impossible to substitute.

The innovator will obtain a sustainable competitive advantage based on an innovation if it maintains a strategy of differentiation against the imitator,

whereas the imitator will obtain a sustainable competitive advantage based on an imitation if it maintains a strategy of price leadership against the innovator.

The explorer will obtain a sustainable competitive advantage based on a local imitation if it maintains a strategy of price leadership vis-à-vis the innovator, and a strategy of differentiation against future imitators.

*Note that the definitions introduced earlier in this blog (such as "innovation = successfully exploited ideas") mostly follow Schumpeter in requiring a positive market impact — a positive benefit, especially in the form of an economic improvement — but there are many alternative definitions including those following Thompson that do not (see research paper for bibliography and details). The only common element among all the definitions of innovation is that it implies novelty.

This table classifies the principal authors in terms of whether they consider the subsequent market or commercial success of an innovation as a necessary factor for innovation.

Schumpeter (1961) dealt with innovation within the theory of economic development as a process of putting into practice new combinations of materials and forces.

Thompson (1967) defined innovation as the generation, acceptance, and implementation of new ideas, processes, products, and services (without mentioning the need for the idea to have a positive impact in the market).